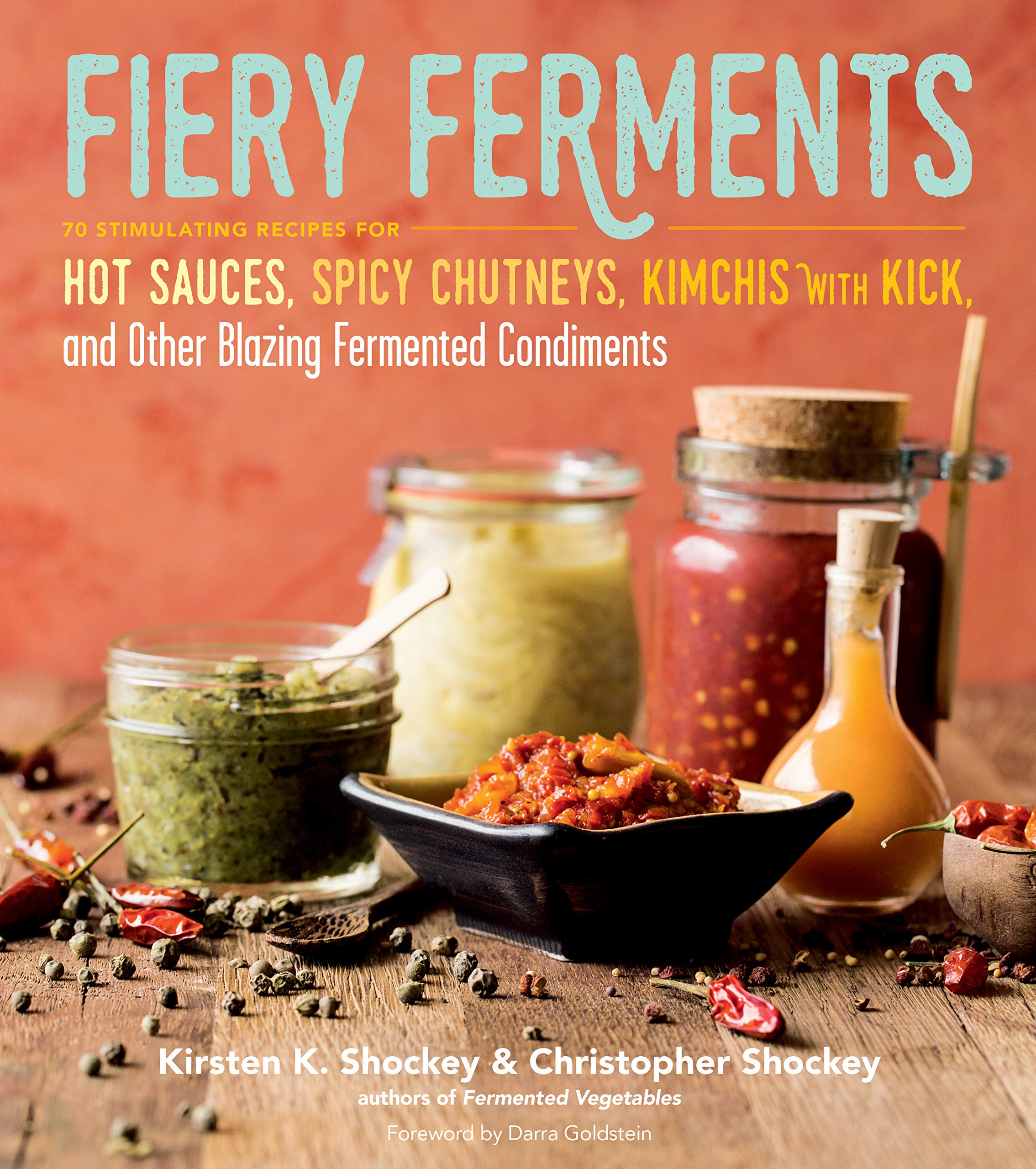

Hot Sauces, for those that love it like we do, is a bit of a drug: you always want more flavour. While the range of fermented hot sauces isn’t quite large in Belgium, making it yourself is a piece of cake. You only need some basic lacto fermentation knowledge and a good supplier of all kind of peppers. While the first part you can learn at Fermenthings or through books like Fiery Ferment, the latter one will be found at westlandpeppers.nl. They offer a wide variety of own grown peppers and are reliable in quality.

Now that you have your knowledge & your supplier, let’s dive into the spicy world of fermenting Peppers and other ingredients.

Why spices?

When talking about hot sauces we must look first at the birth of the use of spices in our cuisine. While we thought for a long-time using spices is something quite recent, recent studies showed that even 6.000 years ago dwellers where using spices to pimp their fish game. Later, around 4.500 years ago proof was found we were already cultivating turmeric, ginger and garlic in regions like New Delhi or the south of China. While most of the spices that were used were based on the soil and cultivation that was around you, when trading roots we’re starting to pop up everywhere, spices where one of the first goods that were traded. The door was open to introduce the main player that will change up the game: Chili Peppers.

Chili Peppers were a game changer, and it’s why we’re talking about Before Chili (B.C) & After Chili (A.C) So when the America’s where discovered by western society an immediate change occurred in the way we looked at spicing our food. For example, Kimchi (or the restaurant variation we know best here in the west) got it’s red vibrant colour only from the 18th century onwards when chilis found it’s way to Korea. Chilis started they conquest of the world and are now a common good in cuisines from around the world.

“Spices were trendy for much the same reason in 1500 as they are now. Once again, people are looking to spices for the elixir of life or a ticket to paradise. And the future bodes well for people who study spices as well as for those who come up with new ways for us to consume them… We are living in a new golden age of spice.” Michael Krondl, The Taste of Conquest: The Rise and Fall of the Three Great Cities of Spices

Why Fermentation?

Well, often when making sauces like chili we see different methods like cooking the peppers, creating a mash. What we prefer is making a fermentation brine. It creates a much more complex aroma for the sauce and makes it possible to change the outcome of your product. Your spiciness becomes more balanced and longer, you can have some notes of acid and sweet throughout the taste of your sauce. Fermentation is not only a good way to preserve, but also to create flavour.

You can find a basic intro about fermentation here [LINK What is fermentation]

Or look more in detail about lactofermentation here [LINK lactofermentation]

Fermenting is a beautiful technique, but keep in mind it has a couple of factors that will alter the outcome of your ferment. Like Meneer Wateetons says in Over Rot, fermenting is like getting ready to organize a war, where you want your bacteria (the good ones) to prevail over the bad ones (giving it mold of all kind of colours for example). To prepare for war you need to have a good view over your surrounding factors, and for fermentation it’s the following:

– The food you give to your bacteria

– The amount or lack of air (Aerobic / Anaerobic)

– The temperature

– The contact with (in)direct light

So when starting a fermentation, like the lactic ones we are going to do here you need to create the following basic environment:

A salty (between 2% and 5% of the total weight depending on the recipe) fluid in an anaerobic jar (air can get out, not in, like a weck pot) , in a dark and reasonable tempered (13 – 18 Celsius) space.

Of course, you can vary on these factors, creating your own ideal environment for a ferment. But this is the one that is a 99% success-rate at our shop for lactofermenting vegetables.

Scoville, Seeds & Getting used to the heat.

Much is discussed about hot peppers, but often the science and biological knowledge behind is forgotten. To determine the hotness of a pepper we all refer to the Scoville unit of measurement (SHU) and varies between 0 and 15.000.000 (5000 for tabasco for exemple, 2.200.000 for the Carolina reaper) and is measured through the dosage of capsaicin that is in each pepper.

While we often think the head is found in the seeds, not a lot of the capsaicin, which produce the heat is found there. Instead it is mostly the white flesh inside where the heat is found. Why go seedless or not in making a sauce is more a question of thickness, pureness and smoothness of your ferment. It will not vary that much in heat.

Strangly also, one pepper will not be as strong as another. Even from the same plant. There are other factors, like the density it was grown, the amount of sun and water that will create a variation between the heat of peppers of the same plant. Finally: you don’t get used to the heat; you just accept faster the fact it’s going to hurt. But who doesn’t like a bit of pain?

RECIPE: Habanero Carrot Sauce

This sauce was based on a recipe in the book of Fiery Ferment, where we used parts of the lemon instead of the juice, to counter a bit of the sweetness of the carrots. Mixing fruits and vegetables in hot sauces is a big win, and can create long lasting and complex tastes.

What also good with hot sauces is that you don’t have to do a lot of cutting, just do some ruff cuts and let it ferment all together and mix it afterwards.

For 500ml hot sauce you will need:

200gr of carrots

3-6 habanero’s

3 gloves of garlic

flesh and juice of 1 lemon

200ml of water

2,5% of salt on the total weight (in this case approximatively 2,5% of 500gr)

Cut everything and mix it together, pack it tightly into a jar that fits the whole without letting to much air on top. Place the closed jar out of direct sunlight for around 14 to 21 days, on a a plate (to catch the fermented juices that will come out if you are using a weck)

When the fermentation is stopped you can get a taste and see how it evolved, it will have a nice acid taste. When mixing it to a sauce, keep the fermented juice on the side and start mixing without it first, add step by step a bit of water till you are happy with the texture, hold onto the rest of the brine to start a next ferment (it’s full of good bacteria, so why throw it out.)

Voila, now you have a good understanding of the basics of what is fermented hot sauces.