A Fermenthings exploration of chili, spice, preservation, and the history of heat.

Heat travels. It moves along trade routes, through migrations, across climate zones, kitchens, and generations. What begins as a plant chemical—capsaicin, sanshool, isothiocyanates—becomes taste, culture, and memory. Around the world, cooks have found ways to stabilise and shape heat into condiments that endure: chili pastes, spiced oils, fermented relishes, dried blends, aromatic vinegars, and pickles that balance fire with salt, sweetness, fat, or fermentation.

This article explores a few of the techniques and preparations used in the Master of Spices workshop, situating them in the wider story of global heat.

1. Three Kinds of Heat

Not all heat is born from chilies. Our mouths feel spice in different ways, depending on the molecule behind it.

Capsaicin: The chili burn

Capsaicin activates our heat receptors. It produces warmth, burn, glow. It is carried by fat and deepens through fermentation. Originating in the Americas, chilies transformed food cultures from Africa to India to East Asia after the 16th century. Today, most global condiments—from sambal to harissa to chili crisp—depend on capsaicin.

Sanshool: Tingling and numbing

Found in Sichuan pepper and its Himalayan relatives, sanshool creates vibration and numbing rather than heat. It heightens aroma and plays beautifully against chili.

Isothiocyanates: Mustard, horseradish, wasabi

These produce fast, sharp, nasal heat. They dissipate quickly and create a clean, bright burn quite different from chili warmth.

Understanding these sensations helps explain why “spicy” is not one idea, but many.

2. The Spice Route and the Movement of Heat

Heat spreads because people move. Trade, agriculture, colonisation, diaspora, necessity, and curiosity have carried peppers and spices across centuries.

-

The Americas gave the world chilies.

-

North and East Africa contributed sun-dried peppers, smoke, and fermented pastes.

-

The Levant and the Arabian Peninsula gave us sourness, citrus, and aromatic blends.

-

South Asia developed systems of mustard, fenugreek, turmeric, and oil-based pickles.

-

East Asia refined chili oils, fermented bean pastes, and vinegar infusions.

Every condiment is a fragment of this long exchange.

Heat is one of the oldest forms of global conversation.

3. Chinese Chili Crisp: Heat You Can Chew

Chili crisp is a northern Chinese evolution of chili-oil traditions, strongly shaped by Sichuan techniques. It is defined not by heat level but by texture.

Shallots, garlic, ginger, and spring onions are fried slowly to coax sweetness and deepen aroma. Dried chilies are bloomed in hot oil. Aromatic spices such as star anise and Sichuan pepper add warmth and perfume. The result is a condiment that is layered, crunchy, savoury, and highly stable thanks to oil and dehydration.

Chili crisp shows how heat becomes richer when paired with sweetness, umami, and slow cooking.

4. Japanese Rayu: Quiet, Fragrant Heat

Rayu (or la-yu) is the minimalist cousin of chili crisp. It began with Chinese immigrants in Japan but adapted into a gentler infusion: toasted sesame oil, dried chili, perhaps a hint of garlic or ginger. It is used not as a sauce but as a whisper of warmth on dumplings, ramen, or cold tofu.

5. Shito: A West African Preservation Classic

Shito from Ghana is a lesson in oil-based preservation. Dried fish or shrimp powder, onions, garlic, ginger, tomatoes, and dried chilies are cooked down slowly until the mixture becomes a dark, concentrated paste.

The power of shito comes from dehydration and oil, two old techniques that protect and amplify flavour. It is smoky, salty, fiery, and deeply umami. Like miso or harissa, it is a cornerstone condiment that shapes everyday cooking.

6. Achar: Salt, Spice, Oil, and Fruit

Achar is a vast family of South Asian pickles that use salt, whole spices, and oil to stabilise vegetables and fruits.

The combination of persimmon (kaki), quince, and a winter vegetable such as daikon shows how sweet, tannic, and earthy elements can coexist in one jar.

Mustard and fenugreek bring bitterness and backbone. Nigella and cumin give aroma. Chili adds heat. Oil creates a seal.

The result is a condiment that sits somewhere between ferment, pickle, and chutney.

Achar is a study in balance: moisture control, aromatic layering, seasonal adaptation.

7. Why We Preserve Heat

Across cultures, spicy condiments serve three purposes:

Preservation:

Salt, fat, acid, and fermentation stabilise freshness.

Intensity:

Heat fades in fresh chili. Preservation concentrates and deepens it.

Identity:

A family’s sambal or achar tastes like their home.

A region’s chili oil tells a story of local crops and trade.

Preserved heat is memory held in a jar.

RECIPES

Chinese Chili Crisp

Crunchy, aromatic, savoury heat preserved in oil.

Ingredients (1 medium jar)

Aromatics

-

4 shallots, thinly sliced

-

6 garlic cloves, thinly sliced

-

1 thumb ginger, julienned

-

2 spring onions, white part only, sliced

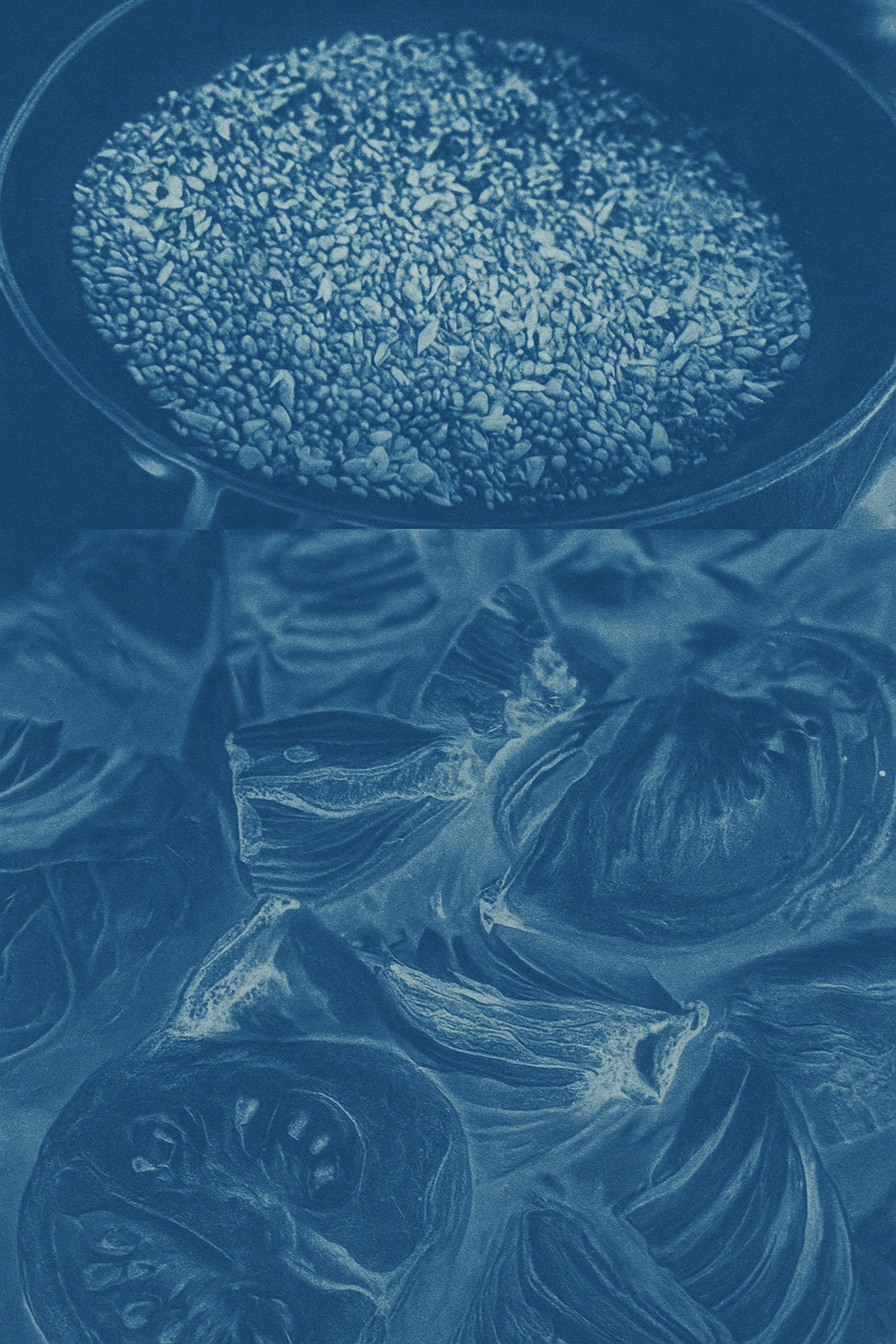

Dry mix (heatproof bowl)

-

25 g dried chili flakes

-

1 tsp Sichuan pepper, lightly crushed

-

1 tsp toasted sesame seeds

-

1 small piece star anise

-

½ tsp smoked paprika (optional)

-

½ tsp salt

-

½ tsp sugar

-

1 tbsp fermented black beans, rinsed and crushed (optional)

Oil

-

250 ml neutral oil (rapeseed, sunflower, grapeseed)

Method

1. Prepare dry mix

Combine chili flakes, Sichuan pepper, sesame seeds, star anise, paprika, salt, sugar, and black beans in a heatproof bowl.

2. Fry aromatics

Heat the oil slowly.

Add shallots and fry until golden and crisp. Remove.

Repeat with garlic, ginger, and spring onion.

Slow frying prevents bitterness.

3. Bloom the chili

Reheat the oil to about 150°C.

Pour directly over the dry chili mixture.

It should foam and release a deep aroma.

Let sit 5 minutes.

4. Combine

Add all fried aromatics.

Stir and let infuse overnight.

Storage

Keeps 2 months in the fridge if solids stay submerged in oil.

Achar with Kaki, Quince, and Winter Daikon

A sweet-tannic-spicy pickle inspired by South Asian oil-based preserves.

Ingredients (1 large jar)

Fruit & vegetables

-

2 firm kaki (persimmon), peeled and cubed

-

1 quince, peeled and diced

-

1 medium daikon, cut into sticks

Whole spices

-

1 tbsp mustard seeds

-

1 tbsp nigella seeds

-

1 tsp fenugreek seeds

-

1 tsp cumin seeds

-

1 tsp coriander seeds

-

1 tsp chili flakes

-

½ tsp turmeric

Salt & acid

-

15 g salt (about 2% of total weight)

-

Juice of ½ lemon or 1 tbsp cider vinegar

Oil

-

150 ml mustard oil

or -

150 ml neutral oil + 1 tsp mustard powder

Method

1. Salt the fruit and vegetables

Toss kaki, quince, and daikon with salt.

Rest 1 hour.

Drain lightly without rinsing.

2. Toast spices

Dry-toast mustard, nigella, fenugreek, cumin, and coriander seeds.

Crush lightly.

Add chili flakes and turmeric.

3. Heat the oil

Heat mustard oil until it just reaches smoking point, then cool slightly.

(If using neutral oil, heat gently and add mustard powder off heat.)

4. Combine

Mix salted fruit and daikon with the spices.

Pour the warm oil over.

Add lemon juice or vinegar.

Stir well.

5. Pack and rest

Pack into a jar, ensuring everything is submerged under oil.

Let sit at least 3 days.

Best after 7–10 days.

Storage

Keeps 1 month in the fridge.

Top up with oil as needed.

Heat is often treated as a simple sensation, something to chase or measure. But when you look closely at the world of spicy preserves, you find a map of human movement, adaptation, and ingenuity. Chili crisps, rayu, shito, achar, sambal, harissa, pepper vinegars, dried blends, and fermented pastes are not inventions of convenience. They are solutions to climate, seasonality, survival, and taste.

Every jar carries a story: a trade route, a harvest, a technique passed down, a personal memory. Heat becomes a way to understand the landscapes and communities behind it. It teaches patience, balance, and respect for the ingredients at hand. It shows how preservation is not only about keeping food alive but about keeping cultures alive.

At Fermenthings, we treat spicy condiments as cultural artefacts with their own logic and ecology. We make them to taste better, yes, but also to learn, to share, to add something meaningful to our kitchens. When you build your own jar — whether a crisp, a paste, or an achar — you are not copying a recipe. You are joining a long tradition of cooks who shaped their environment through craft, care, and curiosity.

Take what you made today and let it change with time. Let it develop. Let it surprise you. Good condiments do not stay still. They travel, ferment, mellow, intensify. And so does our understanding of them.

Heat is only the beginning. The rest is culture.